White Cliffs of Dover

Discover The White Cliffs

The famous White Cliffs of Dover stand guard at the Gateway to England. Millions pass through Dover each year on their journey to or from the continent. In some places over 300 feet high, the White Cliffs are a symbol of the United Kingdom and a reassuring sight to travellers. The Cliffs have been immortalised in song, in literature and in art.

The Geology

On a clear day you can see right across from the Dover cliffs to the cliffs on the French coast at Cap Gris Nez, proof of the continuous strata of chalk.

Around seventy million years ago this part of Britain was submerged by a shallow sea. The sea bottom was made of a white mud formed from the fragments of coccoliths, which were the skeletons of tiny algae which floated in the surface waters of the sea. This mud was later to become the chalk. It is thought that the chalk was deposited very slowly, probably only half a millimetre a year, equivalent to about 180 coccoliths piled one on top of another. In spite of this, up to 500 metres of chalk were deposited in places. The coccoliths are too small to be seen without a powerful microscope but if you look carefully you will find fossils of some of the larger inhabitants of the chalk sea such as sponges, shells, ammonites and urchins.

Since the time of the chalk sea, the chalk has been lifted out of the water by movements of the earth's crust. Most of the shaping of the beautiful chalk downlands we see today took place during the last Ice Age. The latter part of the Ice Age also saw the invasion of chalk by the English Channel. The consequence of this was that Britain became an island.

The Romans

The history of Britain is intricately linked with the White Cliffs.

The first recorded description of Dover describes the scene that Julius Caesar saw in 55 BC when, with two legions of soldiers, he arrived near Dover looking for a suitable landing place for the Roman invasion.

Caesar supposedly "saw the enemy's forces, armed, in position on all the hills there. At that point steep cliffs came down close to the sea in such a way that it is possible to hurl weapons from them right down to the shore. It seemed to me that the place was altogether unsuitable for landing." (Caesar's Commentaries, Book IV.)

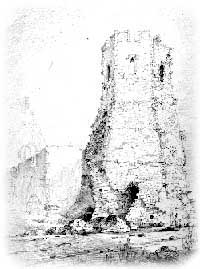

Caesar and his army instead landed just along the coast in Deal and a year later a full scale invasion followed. In order for the Roman ships to navigate more easily, two lighthouses, Pharos, were built on top of the cliffs. One is on the east cliff and stands adjacent to the church of St. Mary, in Dover Castle and is today in an excellent state of preservation. A second Pharos was built on the Western Heights.

The remains of this Pharos were known in the 17thcentury as either the Bredenstone or the Devil's Drop of Mortar. During excavation work for further fortifications of the site in 1861 the foundations of the tower were discovered and left exposed in the wall of the Officers' Quarters.

The Defence of the Nation

The east cliff with its commanding view over the channel is a position of natural strength and has been the site of fortification since the Iron Age. The Castle dates back to the eleventh century but additions and alterations have been made since then, including several notable changes in the twentieth century.

Looking up at the cliffs from Townwall Street, on the approach to the Eastern Docks, you can see signs of massive tunnelling works at various levels in the cliff below the Castle.

The upper level of evacuation took place in Napoleonic times to provide cannon ports: this level of tunnels was used during the First World War as a hospital. During the Second World War this level was used to billet troops during the excavation of Dunkirk. The lower levels housed the operations room for Channel Command during the Battle of Britain and these rooms were used by Winston Churchill as his personal war-time headquarters.

It was at Churchill's insistence that superior artillery positions were maintained along the White Cliffs, leading to the first gun installed being called Winnie. There were gun batteries along the cliffs at St. Margaret's Bay, Langdon Bay, St. Martin's Battery and the Citadel (the Western Heights) and at Capel near Folkestone. The counterbombardment and anti-aircraft gun fire was directed from a control room in the cliff complex.

On the west cliff, known as the Western heights, are two Napoleonic forts linked by miles of ditches. Construction of these began in 1804 and was not completed until the 1860s. The Drop Redoubt, the smaller detached fort, housed a team of Commandos during the Second World War. Their task would have been to sabotage the port in the event of Dover falling to German forces.

The White Cliffs in Song and Literature

In 1941 the White Cliffs became a symbol of the hope for peace expressed in the lines of the renowned song The White Cliffs of Dover by Vera Lynn (words by Nat Burton, music by Walter Kent, 1941).

The most famous reference in English literature to the White Cliffs is in Shakespeare. The scene is so renowned that Dover's Shakespeare Cliff was named after the reference.

In King Lear in Act IV, Scene I, Edgar persuades the blinded Earl of Gloucester that he is at the edge of a cliff in Dover.

Gloucester says "There is a cliff, whose high and bending head looks fearfully in the confined deep:

Bring me to the very brim of it"

Edgar fools the Gloucester into thinking he is at the Cliff edge and describes the scene: "Here's the place! - stand still - how fearful/ And dizzy 'tis, to cast one's eye so low [...] half way down/Hangs one that gathers samphire: dreadful trade!/Methinks he seems no bigger than his head."

Shakespeare's mention of samphire gatherers prompts a diversion from literature to an example of the plant life which abounds on the chalk grasslands and even on the cliff face.

The Rock Samphire, a native perennial with small yellow florets, was once a favourite vegetable, the leaves and stalk were cooked and eaten like asparagus. Samphire gatherers collected the plant by attaching themselves to a rope suspended from the cliff top. In 1768 a highwayman escaped from confinement in the Castle by way of a rope left by a samphire gatherer at the top of the Castle cliffs.

Not all apprehended thieves got away so easily though. In medieval times the cliff overlooking Snargate Street called Sharpness Cliff was a place of execution. The prosecutor had to double as executioner and throw the thief off the cliff.

In 1867, famed nineteenth century English poet Matthew Arnold wrote his beautiful lyric poem 'Dover Beach' about the town, perfectly eptimising the beauty of the Kent coast.

"The sea is calm tonight,

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits:- on the French coast, the light

Gleams, and is gone: the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay."